No courage is needed to pick a fight with a dead man, it can only ever be a war of words [my ones now against his of the past] and as we know, ‘words can never hurt us.’ But it has crossed my mind that the people who invest in and those who sell the dead man’s work to those who invest in it, could get pissed off if I convince even one of you avid followers to denounce this dead man in public and call him a crap artist. But please feel free to do so, I’d love it, just don’t mention my name. Because these guys, the criminally rich, can afford private armies, or specialists at pulling out finger nails or whatever else is required to sow terror among those who question the god-like supremacy of money and those who have most of it. And I’ve heard they have offices, always in the flashiest buildings in town, where a pretty girl ‘manning’ the front desk greets you with a husky voiced, “welcome to Reunion Solutions” or some equally bland name for an organisation that hunts down entire families of those who’ve pissed them off, incinerates them and delivers the burnt remains to the single survivor in a cardboard box. You think I’m making this all up? I wouldn’t put any money on it not being true. For as the late Robert Hughes said—the art market is the second largest uncontrolled market in the world, after the drug market—and he should know, having been in close contact with artists, dealers, curators, collectors and general hangers on in the New York art world since the 60’s. Yes, aren’t we a lovely species that can take art and reduce it to a vehicle for financial gain and self-flattery, reduce meaning to a name and price tag. But I’m getting side tracked, for it is not the buyers of his work that I want to attack first [for the reasons mentioned above and because I’m a coward] that will come at the end of this blog where only the intrepid will arrive. It is the dead man who painted their most valuable pieces of ‘art-means-money’ that I want to attack first, the ‘rotten to the core, or grinding machine’ as he called himself, or ‘devil, whore, world’s leading alcoholic and sacred monster’ as others have called him. Yes, the one and only, FRANCIS L BACON—the painter of the most expensive paintings ever made.

The ‘L’ is of course my own silly addition because I see Bacon as the impresario or at least the ring master of his own freak show, and so deserves that middle initial to his name. Some of the questions one asks oneself when watching a tacky circus [ and all circuses must be tacky] are perhaps these —is the lady on the high wire really naked, did that horse just sing, or did that evil man saw the pretty lady in half and is that blood on his saw and on the floor? And the questions I ask myself in front of a Bacon painting are not dissimilar—is that black, blue or red shape blood, urine or a shadow, why is everyone a contortionist in his paintings or is this a one man circus, and will any of this still matter when I leave the show and walk outside?

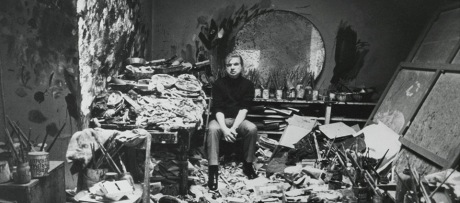

‘Birth, copulation, death—end of story’ was how Hughes summed up Bacon’s view of life. Throw in huge amounts of gambling, champagne dining, drunken pontificating on the meaningless of life, drunken and violent sex, the creation of a studio [so filthy, so chaotic, so cluttered and encrusted with human faeces, rotten food, discarded paint and a thousand other things that it is most probably his greatest work and has actually been recreated as a permanent exhibit in a gallery in Dublin] as well as somehow the production of a surprising amount of precisely and consciously designed paintings, you have the life of Bacon in a single paragraph.

John Berger wrote very astutely about Bacon, in 1952, 1972, and then again at least twice, more than ten years after Bacon’s death in 1992.

Here is an early statement by Berger. “These paintings are haunting because Bacon is a brilliant stage manager, rather than an original visual artist; and because their emotion is concentratedly and desperately private…there is no evidence in his work of any visual discovery, but only of imaginative and skilful arrangement…no new meaning is added in the actual process of painting them…for myself I believe that Bacon’s interpretation of such suffering and disintegration is too egocentric, that he describes horror with connivance and that his descriptions lack not only the huge perspective of compassion but even the smaller perspective of indignation.”

In 1972, Berger looked at Bacon’s work again. “In the portraits of friends like Isabel Rawsthorne, or in some of the new self-portraits, one is confronted with the expression of an eye, sometimes two eyes. But study these expressions; read them. Not one is self-reflective. The eyes look out from their condition, dumbly, into what surrounds them…The rest of their faces have been contorted with expressions which are not their own, which, indeed, are not expressions at all…Normally, likeness defines character, and character in man is inseparable from mind… [But in Bacon’s work] we see character as the empty cast of a consciousness that is absent…Living man has become his own mindless spectre.” Berger continues, “Bacon’s art is, in effect, conformist. It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney… Disney makes alienated behaviour look funny and sentimental and, therefore, acceptable. Bacon interprets such behaviour in terms of the worst possible having already happened, and so proposes that both refusal and hope are pointless. The surprising formal similarities of their work—the way limbs are distorted, the overall shape of bodies, the relation of figures to background and to one another, the use of neat tailor’s clothes, the gestures of hands, the range of colours used—are the result of both men having complementary attitudes to the same crisis.”

And, writing in this century, Berger said… “Bacon’s vision from the late 1930’s to his death in 1992 was of a pitiless world. He repeatedly painted the human body or parts of the body in discomfort or want or agony. In Goya…one listens to the artist’s outrage. What is different in Bacon’s vision is that there are no witnesses and there is no grief.” And near the end of this essay Berger admits to this frightening realisation. “It can happen that the personal drama of an artist reflects within half a century the crisis of an entire civilization.”

All that is left for me to say, all that is left for me to hope for is that when the criminally rich—the ones that define our civilization while destroying it, and who can afford this type of painting and anything else their pitiless selves desire, head off on a space craft to a new world, leaving us with the barely habitable ruins of this one—and they will—I hope they take their fucking Francis Bacons with them.