I’ve just read Orhan Pamuk’s latest novel, The Red-Haired Woman, which swirls a the present day story [1984 to 2015] in and out of earlier ones, in particular Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and the Persian 10thC story of Rostam and Sohrab. Oedipus, as we know, unwittingly kills his father King Laius, marries Queen Jocasta, his mother, and has children by her. And, when he discovers what he has done [largely through his own efforts] he blinds himself with hair pins he takes from the body of his mother who has just hanged herself. But what I had forgotten [and I’ll hazard a guess as to why I’d forgotten this in a minute] was how this had all been set in motion. It all started with a prophecy told to King Laius at the time of Oedipus’s birth, a prophecy claiming that this son would kill him and sleep with his mother. And so the king had the infant’s ankles pierced and bound together so that he could only crawl, then his mother had a servant take him and abandon him on a mountain side, where he was expected to die. But the servant, as so often in stories, was kinder than her mistress and gave the child to a shepherd family [also often good in both truth and fiction] who gave him to the childless king and queen of neighbouring Corinth. So where does the guilt lie, really? Is this a story about patricide and incest or is it about cowardice on the part of Laius and Jocasta, or about fate, or about fears we pass on through old stories, myths and religious scripts.

Reading the story of Oedipus when I was young, or having it read to me, I think I remember having little sympathy with him, so horrified was I by his actions. And the idea that his parents [for whatever quasi-religious or selfish reason] could have wanted him dead, was either so beyond my comprehension or filled my cosseted self with such dread that I blocked it from my memory. For we bring ourselves to every story we read, and of course to every story we write.

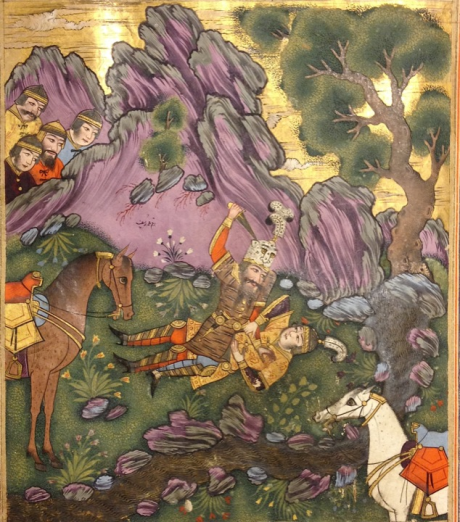

The other story, one that becomes an obsession with Pamuk’s character, Cem, in The Red-Haired woman, is by the Persian poet Ferdowski and is about the great warrior Rostam who, after a mighty battle lasting days, slays the powerful and much younger Sohrab, only to discover that he is actually his son. Poor Rostam we are persuaded to think. Only the story is also not so cut and dried when trying to apportion sympathy, for it tells of the time when Rostam lost his horse while hunting in a foreign kingdom and was invited to spend the night with the king. That night he slept with his host’s daughter, princess Tahmina, who according to the story came into his room and promised to find his horse if he slept with her and so give her a child. He of course does [being virile and a man in love with his horse] leaving behind a jewel that if the child was a girl should be woven into her hair and if a boy tied to his forearm. Now this, in my mind, is the sort of behaviour expected of a solipsistic creep, not a gallant warrior.

But before I get on to Pamuk and the delicate dance of love and misgivings he carried out with his own father [certainly an inspiration for this fascinating novel] here is Philip Larkin’s blunt, humorous and, if read a few times, strangely affectionate poem on the subject.

This Be The Verse.

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

After Orhan Pamuk won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, he wrote a piece he called My Father’s Suitcase and read it at the award ceremony. It is a beautiful essay, the final one in a book of beautiful essays about writing, Istanbul, other writers, his young daughter, another about his father…anything in fact [which means everything in the case of Pamuk] that interested him. If I’d never read Pamuk I’d hope that someone would give me the following piece of advice: read this book of essays, Other Colours, first—get to know the man, trust him. Then read The Red-Haired Woman and either The Museum of Innocence or Istanbul after that. Leave his longer masterpieces, The Black Book, My name is Red and A Strangeness in my Mind for later when you have no doubt that the journey you are taking by reading these will be one to remember, wonder at and learn from. Then try Snow and the extraordinary, The New life.

Writing those words above, it suddenly struck me that perhaps we need more than one father in our lives, especially, but not only when our fathers are often absent as in the case of Pamuk’s. For is it not the job of fathers to perform acts that are memorable throughout our lives and ones we wonder at and learn from. Yet is that not a lot to ask of one man, and have I perhaps adopted Pamuk as my Istanbul and literary father even though we have never met and he is only two years older than me? Perhaps here in lies a good story, a novel, for anything is possible in the world of stories and the world of fathers and sons.

In The Red-Haired Woman, Cem, the protagonist of the first two parts of this three part novel, is sixteen and fatherless soon after the story begins. His father does not die but is jailed once again for his left wing views then starts a new life with another woman. Cem is a bookish ‘little gentleman’ who wants to become a writer but now needs to find work so he can afford to study further. He shows interest in the work of a master well-digger working close to his uncle’s cherry and peach orchard that he is guarding in the summer for a bit of pocket money, and Master Mahmut, much to Cem’s mother’s horror, asks him to be his apprentice on a well he is to dig above a village on the outskirts of Instanbul. Pamuk describes Cem’s leaving his mother like this, “Clutching my valise and affecting the same defiant expression I saw on my father’s face when put on trial, I walked out of the house, saying teasingly: “Don’t worry, I will never go down the well.”

And so, ten years after writing My Father’s Suitcase, here is his latest protagonist clutching that case and behaving like his father. But let me finish telling you more [but not too much] about the story of Cem and the Red-Haired Woman, before ending by looking at Pamuk’s writings about his relationship with his father.

Master Mahmut, Cem, and a local boy Ali start to dig the well on a plateau close to a small town, military barracks, and railway line that runs from Istanbul into the huge expanse of rural Turkey. The deeper they go, digging by hand and hoisting the sand and stone to the surface in a bucket attached to a windlass that Mahmut has built, the closer the multitude of stars in the night sky seem to press down on them, the stronger and more man like the ‘little gentleman’ becomes, and when he sees the alluring Red-Haired Woman walking in the town with what he presumes to be her family, his transition from boyhood to manhood is almost complete. And it is under the affectionate yet strict tutelage of his surrogate father, Mahmut, that this all happens

His erotic obsession gives him energy for the back-breaking work and he fantasises about her daily and walks into town every evening, alone or with his master, to try and catch a furtive glimpse of her again. He is haunted by the sweet look she gave him the first time their paths crossed, as if she knew him, and although older than him he feels they are destined to be together.

He discovers that she is part of a troupe of travelling actors performing in a tent and who call themselves The Theatre of Morality Tales. This novel is nothing if not symbolic at almost every turn. And when he sees her perform, on the night before the day the first part of the novel ends, his life is set on a course that no reader can ever guess.

The second part tells of Cem’s studies [in engineering geology and not literature] his marriage to Ayse, their desperate but failed attempts to have children and the change that occurs in their lives when they accept this and find a passion in searching out and collecting art that illustrates the story of Rostam and Sohrab, even starting a property development company they call Sohrab. Their company goes from strength to strength and he gets in touch with his father who is living in a modest apartment with the woman he left him and his mother for, still surrounded by the now very outdated left wing books that Cem remembers from his childhood. The son has now become the father, and at his father’s funeral, a chance meeting sets Cem’s life on a dramatic trajectory.

The final part of the novel is in the voice of The Red-Hared Woman, thirty years after our first meeting her, and the final paragraph, copied out below, adds a wonderful and thought provoking twist to the story. For we learn that the novel we have just read and reached the end of, has still to be written, and that the writer is…Well, that I can’t tell you.

…“Of course you know best how your novel should start, but I think it ought to be sincere and mythical at the same time, like the monologues I used to deliver at the end of our performances. It should be as credible as a true story, and as familiar as a myth. That way, everybody, not just the judge, will understand what you are trying to say. Remember: your father had always wanted to be a writer.”

Pamuk’s father always wanted to be a writer, so much so that he left his family in Istanbul and went to Paris to live a life that he believed was necessary to become one. But he never became one and as Pamuk writes… Two years before his death, my father gave me a small suitcase filled with his writings, manuscripts, and notebooks. Assuming his usual joking, mocking air, he told me he wanted me to read them after he was gone, by which he meant after he died… “Just take a look,” he said, slightly embarrassed. “See if there’s anything inside you can use. Maybe after I’m gone you can make a selection and publish it.”

But Pamuk does not want to read these bits and pieces written by his father. For he is angry that his father did not take writing seriously enough, that he was too much of a social animal and could not put in the long agonising hours alone in a room with other writers and his own imagination: that his father never quarrelled with his own life. Then he says, seemingly contradicting himself, that perhaps his feeling is not so much anger as jealousy. Nothing is simple between fathers and sons unless we keep it simple and frivolous on purpose. But there will, I believe, always be those moments when something slips out, in a look, a few words. Pamuk captures this beautifully in these lines below.

When he was stretched out on the sofa reading, sometimes his eyes would slip away from the page and his thoughts would wander. That was when I knew that, inside the man I knew as my father was another I could not reach, and guessing that he was daydreaming of another life, I’d grow uneasy. “I feel like a bullet that’s been fired for no reason,” he’d say sometimes.

Pamuk’s father, unlike mine, was often absent, but like mine was always encouraging and never hurtful. His father wanted out from what he perceived as the provincialism of Istanbul, my father saw promise [at first but not later] in a small city in the colonies. Pamuk found, through intense attention, that Istanbul was the centre of his world and wrote lovingly and critically about it and his father. I wanted to flee as soon as possible and treated my father and my place of birth with a terrible indifference.

Is that not the behaviour of a solipsistic creep and not of the true and gallant artist that my father hoped I would become: an artist like his father? And is that not the reason I still try?